Evoking Culture Across Time and Space

Many conversations between Johanna Zetterstrom-Sharp (Horniman Deputy Keeper of Anthropology) and I on identity, motherhood and belonging led to the conceptualisation of the Nigeria60 exhibition.

We discussed what it meant to be foreign in your own country. I guess this question had always plagued me and it was even cemented further in 2006 when I read Chinua Achebe’s ‘Home and Exile’. On page 98, Mr Achebe described in his beautiful prose an exchange that took place between the late Tai Solarin and a post office clerk in London in the 1950s. Solarin was a student in London and he took a parcel to the post office to send home to Nigeria and the clerk whilst trying to figure out the postage fees asked “Nigeria…Nigeria…Is Nigeria ours or French? To which Solarin replied: “Nigeria is yours, madam.”

At the heart of colonisation lies re-writing cultural significance, exploitation and shifting the centrality of power. There is a casual dismissal of another person’s history, sovereignty and culture. Unfortunately, history is seldom documented by both sides and even less so by women. In our conversations we chose to write an imagined history on the day of Nigeria’s independence. As two women, this is how we imagined the morning of Nigeria’s independence.

1st October, 1960

The mood was electric. You could see it, hear it and feel it all around you. Our newly independent nation was fully charged with joy, hope and pride for we did not belong to anybody but ourselves: we were finally ours. As one nation comprised of many ethnicities and kingdoms, we boldly looked forward to be the best. We were fondly known as the giant of Africa and for the first time we could define our future for the benefit and progress of each Nigerian citizen. It was our dream, it was our vision and it was our moment.

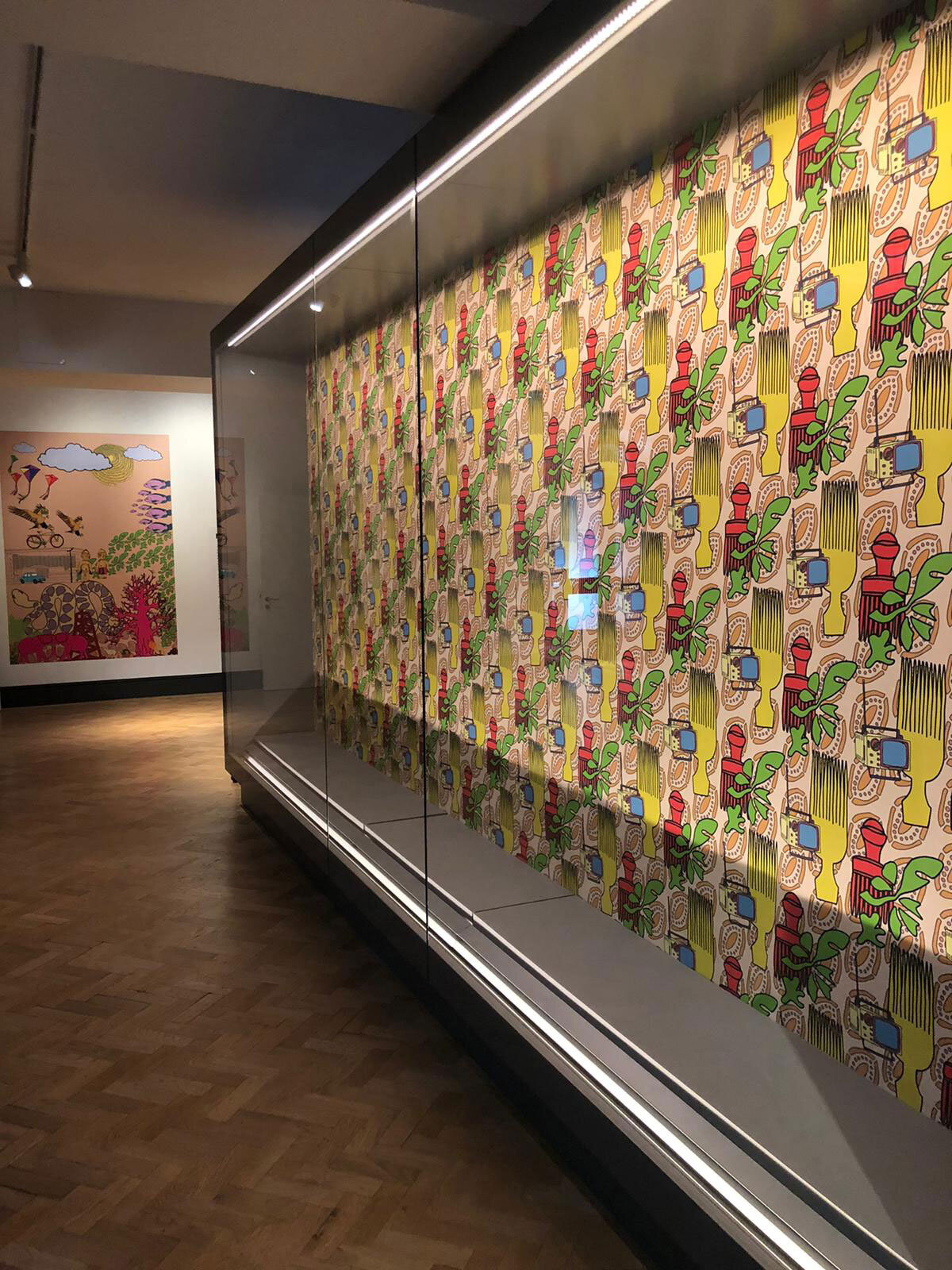

Independence meant that, for the first time, images of leaders printed in newspapers and broadcast on TV-sets were Nigerians; faces speaking about us, for us. Our children could see themselves in the roles they aspired to, and in the future worlds they imagined through play.

What does it mean to be free?

On the morning of the 1 October, 1960, a family sit down to breakfast. The radio is tuned in to the news. A child asks her mother, “What does it mean to be free?”

“Independence is freedom. Freedom to be yourself, freedom to pray to your gods, to speak your language and wear your hair and traditional clothes without reprimand. Freedom is not having your country occupied and ruled by another. Not having your culture, artefacts, kings and queens dismantled. Freedom is priceless.”